The fabled 4% rule, is one of the first “rules” new converts to the Financial Independence Retire Early movement run into. The “rule” suggests that you can safely withdraw 4% of your investment portfolio annually in retirement, adjusting for inflation, with a high likelihood for a traditional retiree to not run out of money before they die.

The “rule” suggests that you can safely withdraw 4% of your investment portfolio annually in retirement, adjusting for inflation, with a high likelihood for a traditional retiree to not run out of money before they die.

Sounds simple enough right?

You would think so, but not a single week goes by where I don’t run into a misinterpretation. One of my hobbies is to go around the internet and let people know they are wrong.

Even one of the OGs of the FIRE movement Mr Money Mustache perpetuates the confusion through his over-simplification and reliance on adding in multiple backup plans.

However, you, FAANG FIRE reader, are not most people. So let’s all get on the same page so you too can go around the internet and tell people they are wrong.

The Foundational Literature

There are two foundational pieces of literature that most recognize as unintentionally birthing the 4% rule. The two pieces of work both utilized historical stock market returns to establish potential retirement withdraw rates that wouldn’t run out of money. For Part 1 of this series we will talk about one of the first usages of a 4% safe withdrawal rate by Bill Bengen and his method of using actual historical returns. In Part 2 we will cover how 3 professors from Trinity University expanded on this analysis to really cemented 4% into the retirement planning dogma.

Nothing is more satisfying than being able to go to the source to better understand from the original authors perspective. These are the best links I have found that include the original publications.

Bill Bengen who published his research in the October 1994 issue of the Journal of Financial Planning. (PDF Link)

Philip L. Cooley, Carl M. Hubbard and Daniel T. Walz of Trinity University (PDF Link)

Bill Bengen and the Origins of 4%

The origins of the 4% rule are found in a few paragraphs within a 1994 article by Bill Bengen in the Journal of Financial Planning.

“For a client just beginning retirement, determine first the "safe" withdrawal rate. Do so by computing the shortest portfolio life acceptable to the client (generally the client's life expectancy plus 5 or 10 years, depending on the conservatism of the client). Next, using the charts for a 50/50 stock/bond allocation, determine the highest withdrawal rate that satisfies the desired minimum portfolio life. For a client of age 60–65, this will usually be about 4 percent. The withdrawal dollar amount for the first year (calculated as the withdrawal percentage times the starting value of the portfolio), will be adjusted up or down for inflation every succeeding year. After the first year, the withdrawal rate is no longer used for computing the amount withdrawn; that will be computed instead from last year's withdrawal, plus an inflation factor.

…

Assuming a minimum requirement of 30 years of portfolio longevity, a first-year withdrawal of 4 percent, followed by inflation-adjusted withdrawals in subsequent years, should be safe. In no past case has it caused a portfolio to be exhausted before 33 years, and in most cases it will lead to portfolio lives of 50 years or longer. ”

Bill Bengen’s Goal

Bill Bengen’s goal in his article was to “present simple techniques planners can use immediately in their practice in advising clients how much they can safely withdraw annually from retirement accounts”. Bill was encouraging advisors to move away from simple market return averages and learn from what withdraw rates survived the worst 30 year periods in recent stock market history. He never set out to create a “rule”, but simply wanted to help advisors learn how to think about withdraw rates while factoring in the actual historical data.

The key innovation that Bengen brought to the table was utilizing historical stock return data to backtest different withdraw rates. He really honed in on identifying a withdraw rate and portfolio allocation that would survive the 3 worst stock market crisises that had existed (prior to 1994 when he originally published the work).

Ever the astrology buff, Bengen named the three crisis "Big Bang," the "Big Dipper," and the "Little Dipper." Your gut might tell you that the worst situation for the 4% rule must have been the great depression, but in reality that was the 3rd worst.

Here are the three periods as described by Bengen:

The "Big Bang" of the 1973–74 recession was the most devastating because it occurred during a period of high inflation. Not only did investors suffer large paper losses in their portfolios, but the purchasing power of what remained was reduced substantially. It was a frightening period for investors.

The "Big Dipper" of 1937–1941 featured a stock decline almost as great as the "Big Bang," but it occurred during a period of moderate inflation and some-what higher bond returns. Therefore, its impact on portfolios was not as severe, though it was still substantial, particularly as it followed the "Little Dipper" by only half a decade.

The "Little Dipper," of course, was the early Depression years. It may sound odd to list its impact as only third behind the previous two events, given the huge decline in stock prices that occurred. However, as you can see from Table 1, the early years of the Depression was a deflationary period, so the impact of the decline in stock values was cushioned by an advance in purchasing power for the dollar, as well as by modestly positive bond returns.

4% Rule Example

Imagine a 65 year old with $1,000,000; let’s call them Pat. Pat wants to know how much they can withdraw from their $1,000,000 porfoltoio without running out of money.

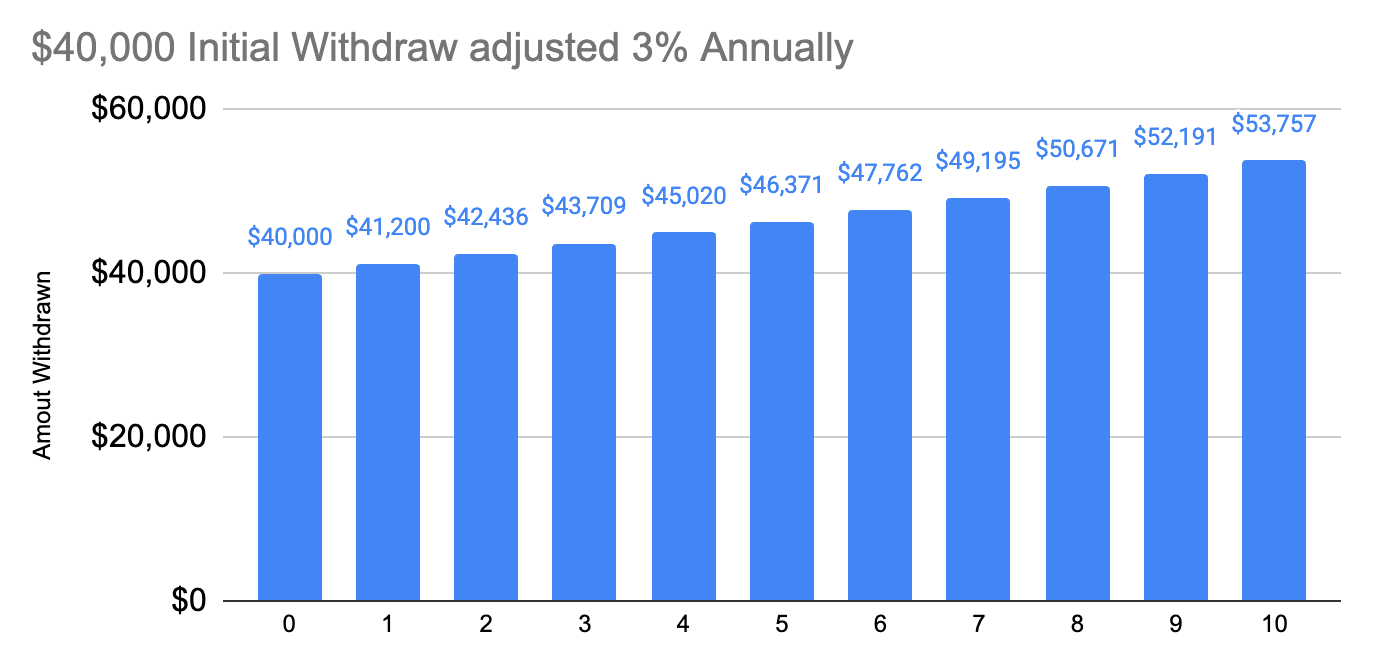

If Pat had $1,000,000 invested roughly 50/50 stocks and bonds, the 4% rule says that Pat can withdraw $40,000 in Year one. This is the only time Pat will calculate 4% of their portfolio. From here on Pat will base future withdraws off the amount they withdrew the prior year and adjust it for inflation. Historically inflation has averaged ~3% but can vary a bit year to year, 2022 for example saw very high inflation. The goal of the inflation adjustment is to allow Pat to always have the same buying power that they had in year 1 of retirement.

If inflation was 3% in year one and 5% in year two Pat’s withdraws would look like this:

Year One: $40,000

Year Two: $40,000 x 1.03 = $41,200

Year Three: $41,200 x 1.05 = $43,260

Here is a visual showing a static 3% inflation. Over 10 years the withdraw amount increased from $40k to $53k. Inflation is a critical component to this analysis.

Important Call Outs

4% isn’t a “rule”

Research was based on 60-65 year olds with a traditional ~30 year retirement window, assuming typical life expectancy +5-10 years

The asset allocation used had at least 50-75% stocks and the remaining in bonds (or more precisely “the historical record supports an allocation of between 50- percent and 75-percent stocks as the best starting allocation for a client. For most clients, it can be maintained throughout retirement, or until their investing goals change. Stock allocations below 50 percent and above 75 percent are counterproductive.”

The goal was “making it through retirement without exhausting their funds”, ie running out of money

The initial withdraw is 4% of the portfolio in the first year and then it is “adjusted up or down for inflation every succeeding year. After the first year, the withdrawal rate is no longer used for computing the amount withdrawn”

You are actively selling your capital and there is nothing about maintaining the same overall portfolio value that you started with

In most cases a 4% withdraw rate “will lead to portfolio lives of 50 years or longer”.

It doesn’t factor in taxes or fees

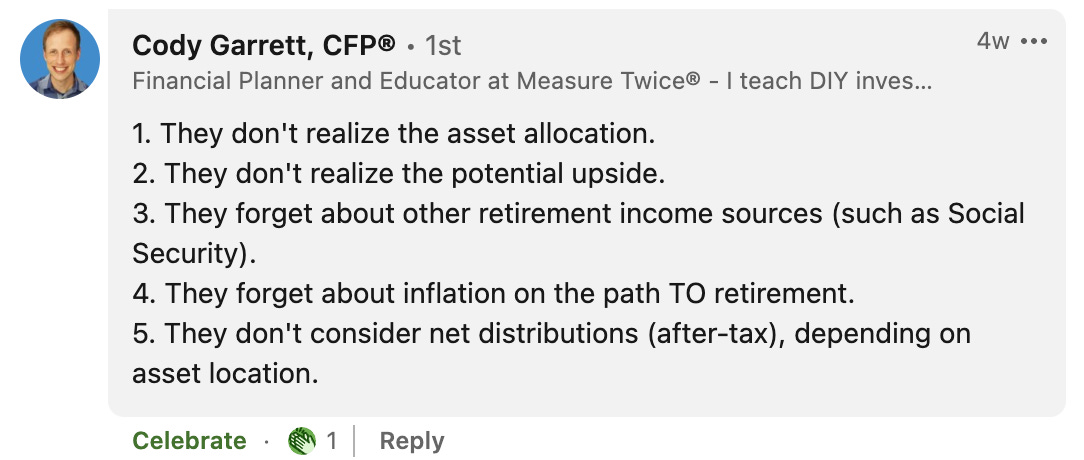

I asked on my LinkedIn what other myths people had on the 4% rule (you should follow me on LinkedIn btw, I post a few times a week inbetween longer newsletter posts).

Certified Financial Planner, Cody Garrett added a good collection:

Let’s go through these together with what we learned so far:

They don’t realize the asset allocation.

“the historical record supports an allocation of between 50- percent and 75-percent stocks as the best starting allocation for a client. For most clients, it can be maintained throughout retirement, or until their investing goals change. Stock allocations below 50 percent and above 75 percent are counterproductive.” Bengen used intermediate term treasuries as his bond holdings.

They don’t realize the potential upside.

Bengen found that most scenarios led to portfolios lasting >50 years. A 4% rule is all about avoiding the worst case scenarios.

They forget about other retirement income sources.

The original Bengen article didn’t factor in any additional income. The most common one being social security, which many FIRE planners don’t count on, it is still a short coming to assume $0.

They forget about inflation on the path TO retirement.

We covered how important it is to adjust each withdraw amount annually by inflation. Cody rightfully reminds us that we should make sure we are factoring in inflation while setting your portfolio goal. If you started planning for a $1,000,000 goal, in 20 years that $1,000,000 will be significantly less than you originally planned.

They don’t consider net distributions (after-tax), depending on asset location.

Taxes are not factored in at all. Which means that where you withdraw your money in retirement isn’t touched on. I touched on “asset location vs asset allocation” in a prior newsletter.

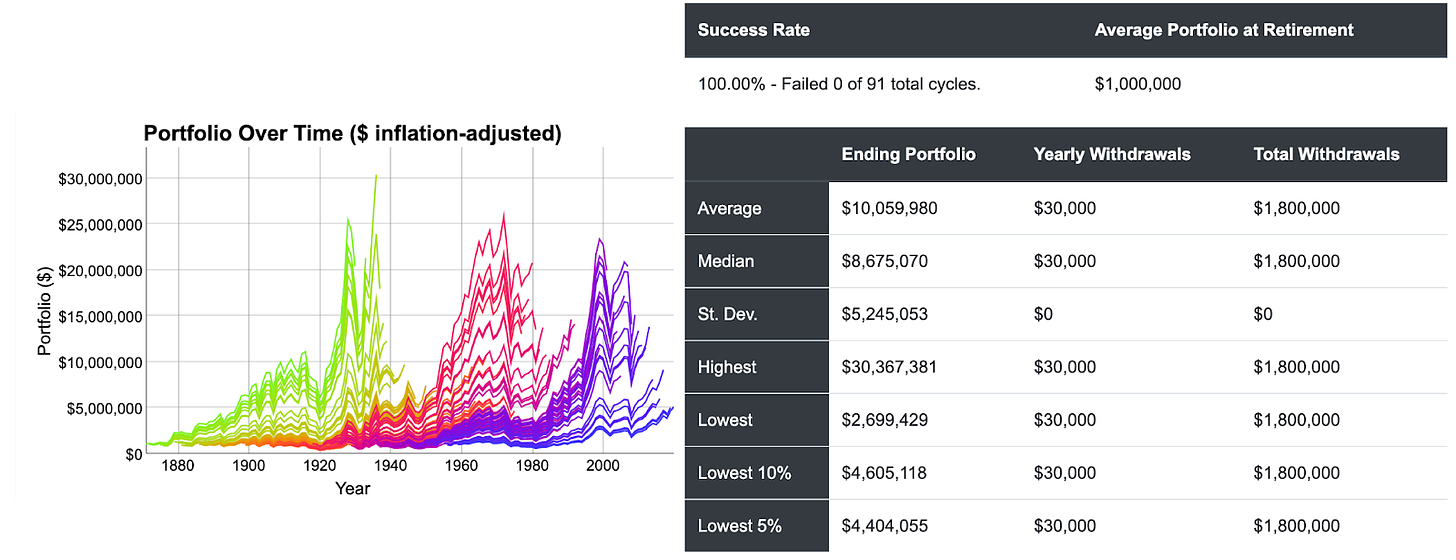

I am personally much more conservative and use a 3% withdrawal rate goal in my own calculations. The desire for financial stability is one element driving this, but with an early retirement pushing 60 years I would rather work a few more years than risk a fail state. Another way to calculate a 3% withdrawal rate would be to multiply my desired spend during FIRE by 33.3. The magic here is that there isn’t a single period in US history where the 3% rule has ever failed. Here is a simulation courtesy of one of my favorite FIRE tools, cfiresim.

You can read more about my own personal strategy in determining “My Enough Number”.

-Andre